|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

Analysis of changes in the estimated cost of the skylab program: https://www.gao.gov/assets/b-172192.pdf

Commercial LEO destination concept of operations: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20230002770/downloads/ATTACHMENT%201%20CLDP-WP-1101_ConOps_Final.pdf

International space station transition report: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2022_iss_transition_report-final_tagged.pdf?emrc=4c4497

CLD requirements and standards: https://govtribe.com/file/government-file/80jsc023cldprequirementsandstandards-1-cldp-req-1130-and-annex-1-dot-pdf

ISS vibration: https://gipoc.grc.nasa.gov/wp/pims/handbook/

As you probably already know, the international Space Station is getting old, and it is currently scheduled to be deorbited in 2030, though that might be extended.

That will leave NASA with no space station in earth orbit, and NASA has some things they want to keep doing there, including:

Continuous US presence in orbit

Further scientific investigation related to deep space human exploration, such as crewed missions to mars.

Sponsoring advancement of technology and systems for deep space human exploration.

The obvious solution is ISS version 2

There are some problems with building a new version of ISS...

The first problem is that the ISS operational budget is about $3 billion a year, and with Artemis heating up and moon landers to pay for, NASA simply doesn't have the budget to support building and launching a new space station, and congress is unlikely to give them more money.

You, in the back. Put your hand down - I'll talk about the lunar gateway space station in a future video.

More importantly, as is often the case, congress would not choose to build a new international space station.

They actually don't say that, what they say is that extending ISS beyond 2028 will significantly slow down the scheduling of crewed missions to Mars.

How cute. Congress actually thinks that we have a crewed mission to Mars program, or that NASA can come up with such a plan in the 2030s.

The act specifically requires the following:

(read)

The goal is to build something NASA has started calling "the low earth orbit economy". And that's something I think most of us would support, at least as an abstraction.

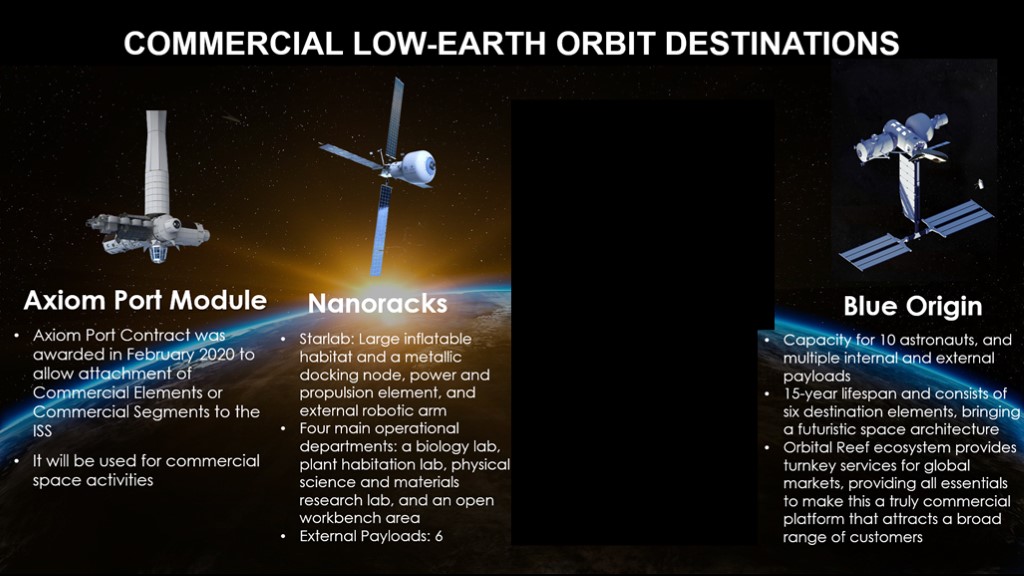

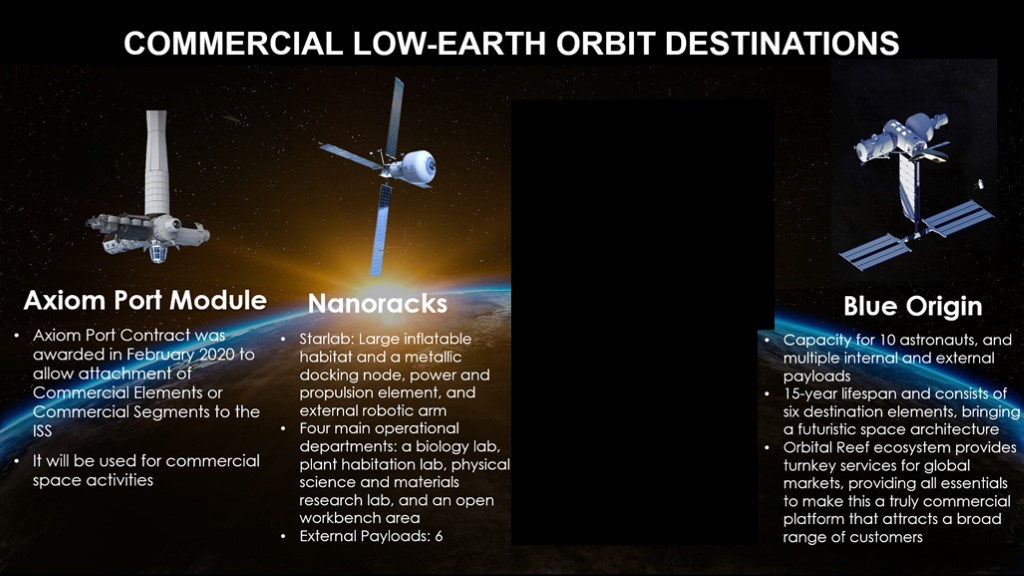

And so we have the commercial low earth orbit development program. Here's what NASA is planning...

They plan to buy time for at least two NASA crewmembers per year aboard commercial space stations. This is an "anchor tenant" concept, where the assured NASA business enables the providers to build, launch, and operate their space stations profitably.

Their plan is to continue the microgravity and biomedical research that they have done on ISS and to add in technology development for exploration, which you can read as "Moon bases and Mars missions".

They also assert/hope that private astronauts would visit for research or tourism.

Early proposals have generated some very impressive slides, but since then, there hasn't been much progress and in fact, in 2023, Northup Grumman abandoned their own plans and decided to join the Nanorack Starlab team.

But there's a deeper problem, and it's pretty simple. These commercial stations do not make financial sense for the private companies that would launch them.

Businesses exist to make money, and what is true for your local store is also true for space stations

It's time for a quick look at investment and returns.

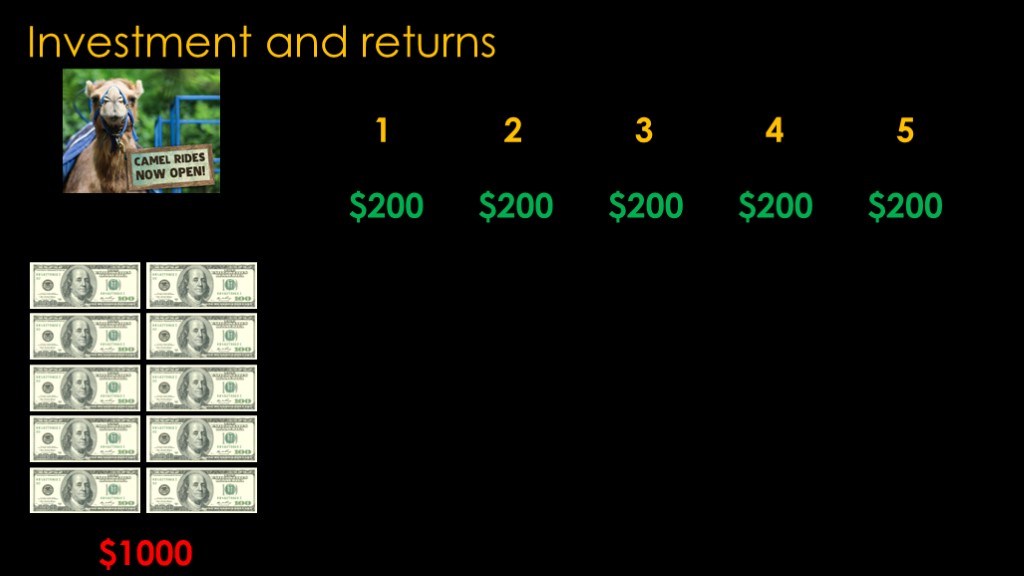

Let's say that your brother-in-law is starting a new business and wants to borrow $1000.

He says that he will pay you $200 each year for 5 years. Do you give him the money?

You probably have a gut feeling based on the numbers, and my guess is that your answer is probably "no", unless you are especially fond of your brother-in-law or camels.

You put in $1000 dollars and in the best case, you only have $1000 after he makes the last payment. From a business perspective, this doesn't look very good.

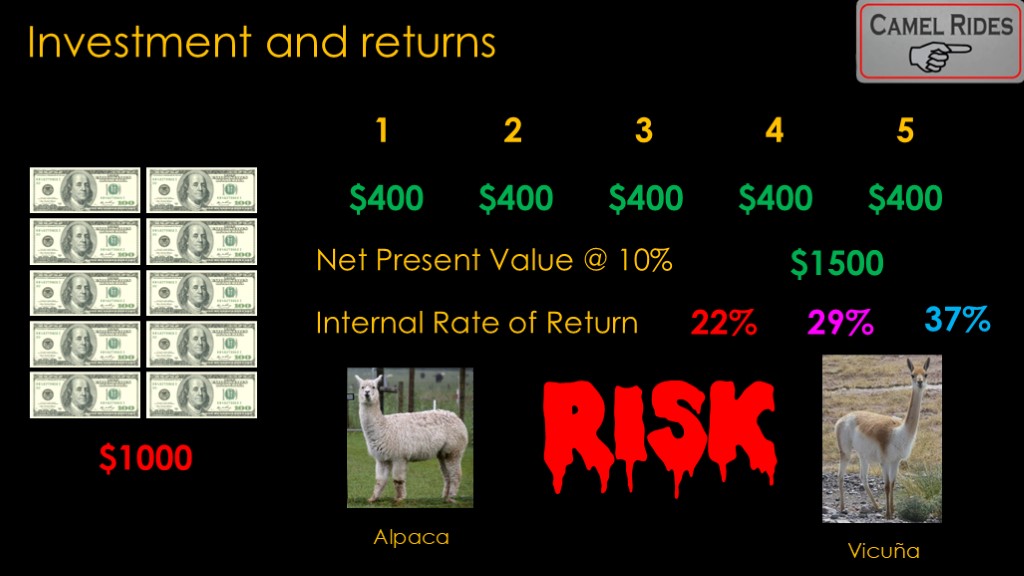

If he offers $400 a year, that's obviously a better deal - you invest $1000 and get $2000 back. But is it good enough?

What we need is way to evaluate projects in a more objective way.

There are two common ways to look at this.

If we assume that inflation is 10% a year - that our money is worth 10% less every year - we can calculate that those $400 payments are worth $1500, so you will make money. This is called the "net present value" approach.

I prefer a different approach, known as the internal rate of return. You can think of it as "how bad would inflation have to be for this investment to break even?". In this case, the internal rate of return is 29%, which makes it seem like a comfortable investment. It would be better than an investment that returns only 22% and worse than one that returns 37%.

But there's a big scary factor that we haven't considered, and that is the concept of risk. How confident are we that we will get that $400 every year?

That is where things get difficult. Perhaps the market in camels is saturated in his area and he should consider focusing his love of camelids such as the alpaca or even the vicuña. Unexpected things might happen - feed or insurance prices may go up, or there may be a breakout of camel flu.

Generally speaking, investments that have low risk have a low rate of return and investments that have high risk require a high rate of return.

If we want to evaluate the investment and return on commercial space stations, we'll need to understand the details of what NASA is proposing.

What is NASA's model for commercial space stations?

The first step is that the provider builds the space station. What kind of space station?

NASA details that in the 41 page CLD concept of operations documents, the several hundred page requirements and standards document, and the long list of references in those two documents.

This program is about doing everything "the NASA way", and to put things simply, your space station must meet ISS module standards. I'm sure many of these standards make a ton of sense, but this is not "design a commercial station", this is "design a NASA station", and NASA will be validating that you have met all the requirements. If you have other ideas about how things should be done, you'll run into the same sort of issues that SpaceX had with commercial crew.

In return for following this standard, NASA will presumably kick in money to help pay for the design construction of the station, but the partner will be required to invest a lot of their own money.

The provider pays to launch the station in orbit, and then NASA is interested in using it. The responsibilities between NASA and the provider are clearly defined.

NASA provides astronauts, money for the astronaut's visit, and oversight of station operation.

The provider provides literally everything else.

NASA enumerates this as:

(read)

This is the all-inclusive exclusive island hideaway space station model.

NASA says the goals of this approach are to maximize partner authority, autonomy, and control over mission operations and to minimize NASA operational involvement.

For crew transport, the vehicles must be certified by the commercial crew program, the FAA, or some future agency.

#2 and 3 don't currently exist, so the effect of this requirement in the short term is to limit crew transport to crew dragon and perhaps starliner if/when starliner is certified.

Cargo will be like the commercial resupply program.

Just to emphasize, NASA isn't buying either of these services; they are part of the all-inclusive orbital package that NASA wants to buy.

Following the all-inclusive space retreat model, the station must serve as: (read)

There are a long list of systems that need to be provided for this, and they all must meet NASA specs.

The roles and expectations for the NASA astronauts and crew members are fairly clear and quite a bit different than ISS.

(read)

The ISS model has 4 astronauts who do everything, and that makes it very easy to load balance across the team. If you need to unload a vehicle, the whole team can pitch in and get it done quickly, and it's easy to deal with rest days and time off.

The model they are proposing has a really obvious issue. Everybody on station has to have time off to sleep and exercise and days off. That means that the provider needs not 1, but 2 crew members to keep the station up and running. The cost of these crew members will be factored into the costs of the station.

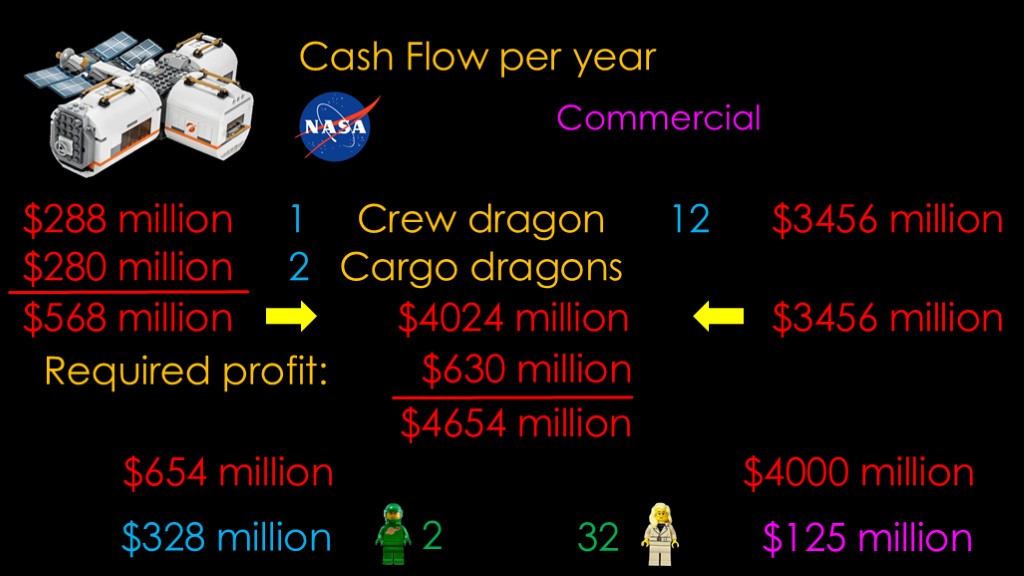

I think we now know enough to play around with some numbers to see if we want to be part of the program. These numbers are for illustration purposes only as we do not have any real details.

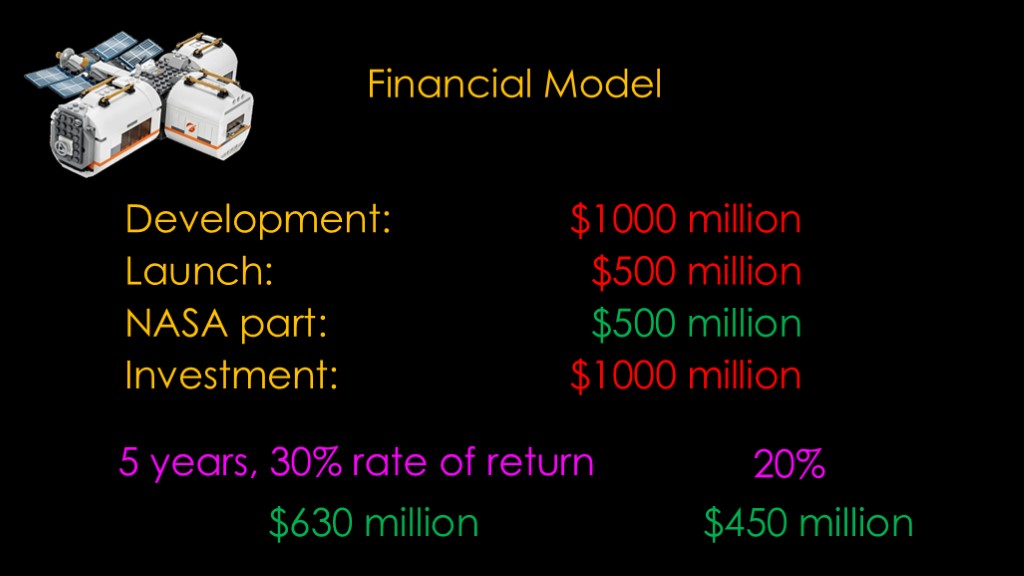

Our station costs $1000 million dollars to develop and $500 million to launch. Just to keep things simple, I'm going to assume that NASA pays $500 million for the launch, leaving us with an easy to understand $1000 million investment that is spent at $250 million per year over four years.

If we've decided that we only want to be in this business if our model says we can get a 30% return on investment for 5 years, we are going to need a net profit of $630 million each of those 5 years. That is a *lot* of money considering the NASA budget for ISS is only about $3 billion per year, and remember that this is the profit we need above our yearly costs. Also remember that NASA wants to have more than one commercial station.

Maybe you think that 20% should be a good enough rate of return. That bumps the required net profit down to *only* $450 million per year.

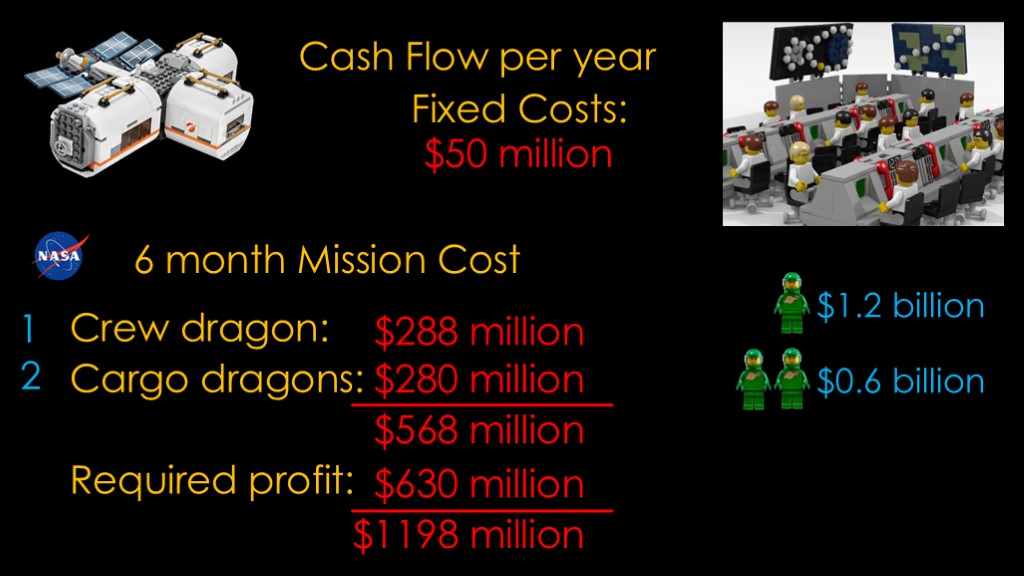

What does the yearly cash flow look like, and is it feasible to net $630 million per year?

We have fixed costs - we need a mission control with a full-time crew, we need backing engineers, we need people to work with NASA and other customers. I'm going to throw the number $50 million at that. And honestly, that doesn't seem very bad - in aerospace terms, $50 million is not a ton of money. Compared to the other costs that we are going to discuss, that amount doesn't really matter.

Looking at the costs for the 6 month missions that NASA wants to fly, that's going to take 1 crew dragon and 2 cargo dragon flights. The crew dragon costs around $288 million and the two cargo dragons add another $280 million, so the total is $568 million.

We are only interested in doing this if we make our required profit of $630 million, so we add that in and get about $1200 million.

That's what we would charge NASA for 1 astronaut spending 6 months on research along with the two support astronauts.

The obvious thing to do is to send 2 researchers, as that will cost pretty much the same amount and half the per researcher price.

Can we save money on the transportation? Maybe, but note that our flight rate is less than what SpaceX is currently flying to the ISS and they have to prove to NASA that they are still crew certified, so there's probably not a lot of room there. Worse, we are absolutely beholden to our transportation company. If they bump up their prices, we are in trouble. If they are grounded, we're in trouble. Etc., etc.

Can we make the numbers better with commercial clients?

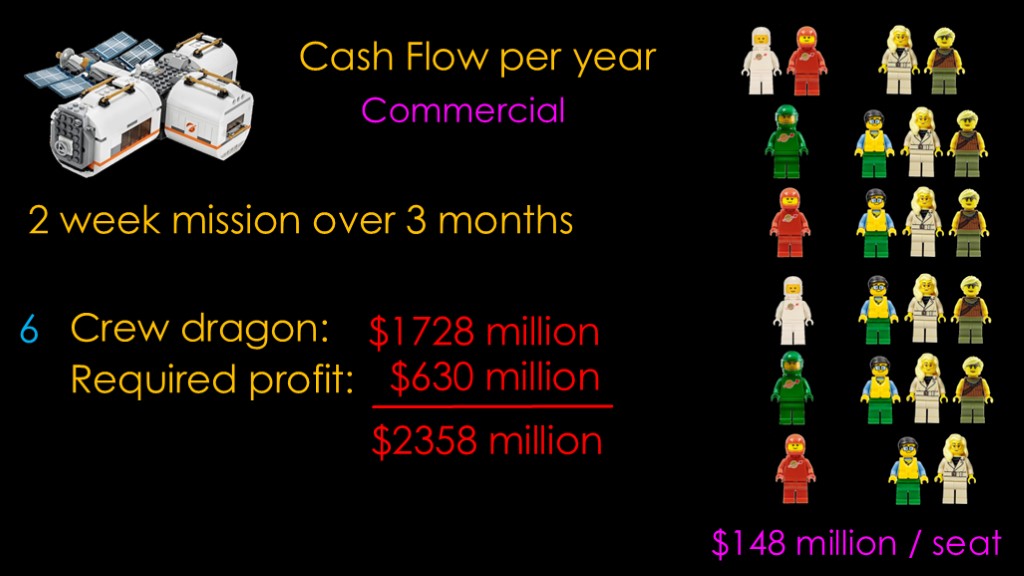

First, will anybody buy that $600 million dollar extra seat to send somebody to space for 6 months? The answer to that is probably "no", so we need shorter missions. Let's see how two week missions work out for a 3 month timespan.

For our first launch, we fly with two of our astronauts and two tourists for a two week stay. The next group launches with one astronaut and three tourists, and we start doing astronaut rotation to always keep two on station. We do four flights with 3 tourists, and then the last flight only has two so that we can bring both astronauts home.

That gives us 16 tourists across 6 flights.

We are only going to be flying Crew Dragon on the assumption that the flights are short enough that we can carry both people and expendables. The cost for those flights is $1728 million. Add in our profit, and we get $2358 million, which comes out to about $148 million per seat.

We will somehow need to have SpaceX figure how to fly a crew dragon flight every 2 weeks.

Oh, and why did I limit it to tourists?

Well, I can see some countries springing for this mission, and I guess I'd call them "governmental tourists". What I don't think we'll see is any researchers because you can do a ridiculous amount of research on the ground for $148 million.

What if we can support a station that has 6 months with NASA astronauts, 6 months with tourists. This is a bit complicated, so bear with me...

The 6 month NASA visit requires 1 crew dragon and 2 cargo dragons, for $568 million.

The 6 month tourist season requires 12 crew dragons for $3456 million - and when we add that to the NASA cost, we get $4024 million. Add in our profit requirement, and we get $4654 million.

We somehow need to allocate that cost across the two programs to come up with a price. I'll just do it proportionally, and we end up with $328 million for each NASA astronaut that is there for 6 months and $125 million for each of the 32 tourists.

That's the plan. But is it a good plan?

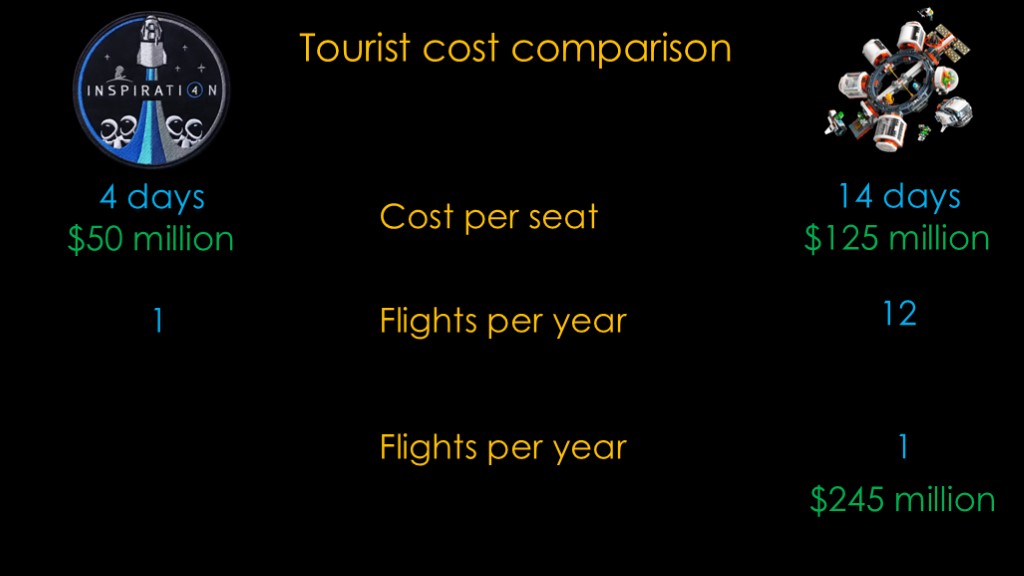

Let's compare the tourist cost of a space station visit to the alternatives.

We decided that the cost per seat for our space station was $125 million.

The obvious alternative is a free-flying crew dragon mission.

The cost for inspiration 4 was less than $200 million, which puts the cost per seat at around $50 million. That's for only 1 flight per year.

The inspiration 4 flight is only 4 days in a small capsule, while our space station is a full 2 weeks in a much bigger station. But is it $75 million per person better? That seems like a hard sell.

Inspiration 4 was a one-off mission, and while SpaceX might be subsidizing the cost, we know that the Axiom flights to ISS are perhaps $55-60 million per seat. Crew dragon flights is a very good model; SpaceX is reusing the infrastructure that is already paid for through the NASA flights and can set their price based on the incremental cost to do another flight and still make money.

If nobody wants to do a dragon flight in a year, it doesn't cost them anything, and if there turn out to be 4 flights of people who want to do this every year, they can scale up.

Our space station tourism model is horrible; the $125 million number depends on us finding 32 people who want to fly with us on 12 flights a year.

If we only fly one mission a year, we need to get $245 million a seat to make our required profit. That *is not* going to happen.

This tourist model is broken. I don't see any world in which we can get even 16 people a year to fly for those prices.

Which brings us back to the NASA model.

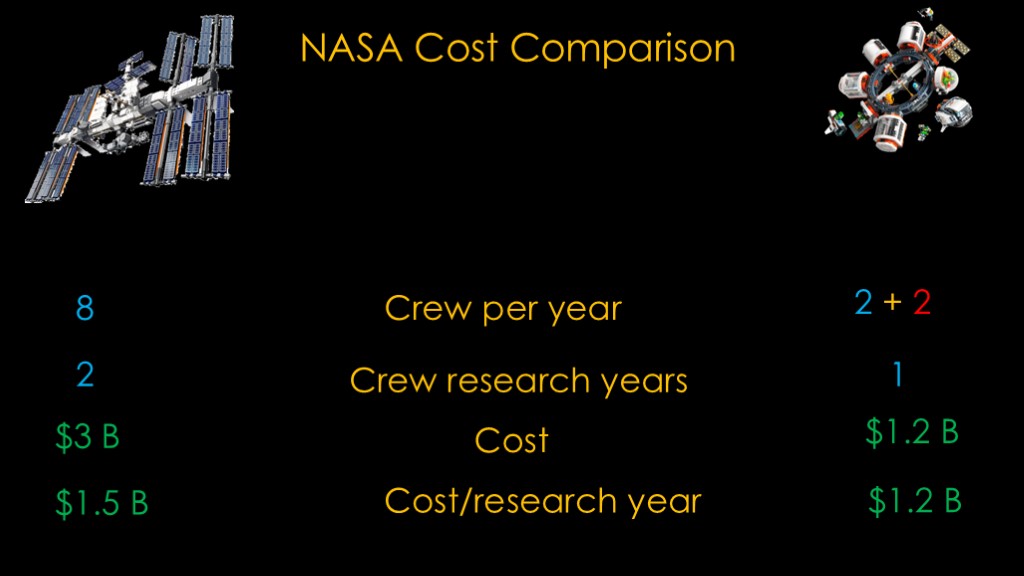

For the ISS, NASA has optimized their costs well by maximizing the utility of the very expensive crew transport flights.

NASA flies two 6 month missions with 4 crew on each mission. Roughly half their time is spend on maintenance and operations, giving then two crew years to do research every year.

For the commercial stations, NASA wants to fly one astronaut for a 6 month stay. Given that adding an extra astronaut means a small increment in cost, I'd expect they would fly 2 , and they would be mostly free to do research, which gives NASA 1 crew year of research.

The cost for the ISS is about $3 Billion, while the charge to NASA for our station is $1.2 Billion, given us $1.5 billion per research year for the ISS and $1.2 billion per research year for the new station.

This ignores the development cost that we said NASA would be paying part of.

So maybe it's a little better, but it's not a lot better. More than half of the ISS cost is transportation, and while NASA spends a lot operations, they have an existing station and don't need to make a return on the construction costs to make the investment worthwhile.

You may have noticed that I didn't talk anything about commercial research and manufacturing and how they might occur on our low earth orbit space station.

The problem is that there is no killer app in these areas at the current transportation costs, and we know this because if the app existed, it would be flying already.

But that is a subject for a future video...

I had originally intended to talk in a lot more detail about what each of the 4 - now 3 - groups are planning with their stations, but as I dug deeper I realized that the concept didn't really make much sense.

The big issues that I see are:

NASA's specified level of participation is insufficient to make the economics of a private space station work.

ISS costs a lot, and NASA already needs to fund the deorbit vehicle. It's likely that commercial funding will be slow, and that makes a poor case for the providers.

Transportation is just too expensive. If you are NASA you can pay those kinds of prices but it's very limiting.

Building a station and operating it are very different businesses, like building a hotel and operating one. The companies who can build a station do not have that sort of experience.

NASA wants the providers to build an ISS-like station and take on the bulk of the financial risk.

The reality is that the current approach isn't workable, and reportedly NASA has already iterated on it without getting to a better place.

The cost structure, the NASA requirements, the overhead of running a station, and the commercial need to make a profit all seem very hard to reconcile. The non-NASA market does not exist and the current transportation costs seem to make it unlikely.

Predicting the future where congress is involved is always difficult, but I see two likely outcomes when ISS is gone.

The first is that NASA builds an ISS version 2. It would likely be smaller than the ISS, but since your current transportation system flies four astronauts, it needs to be sized for that.

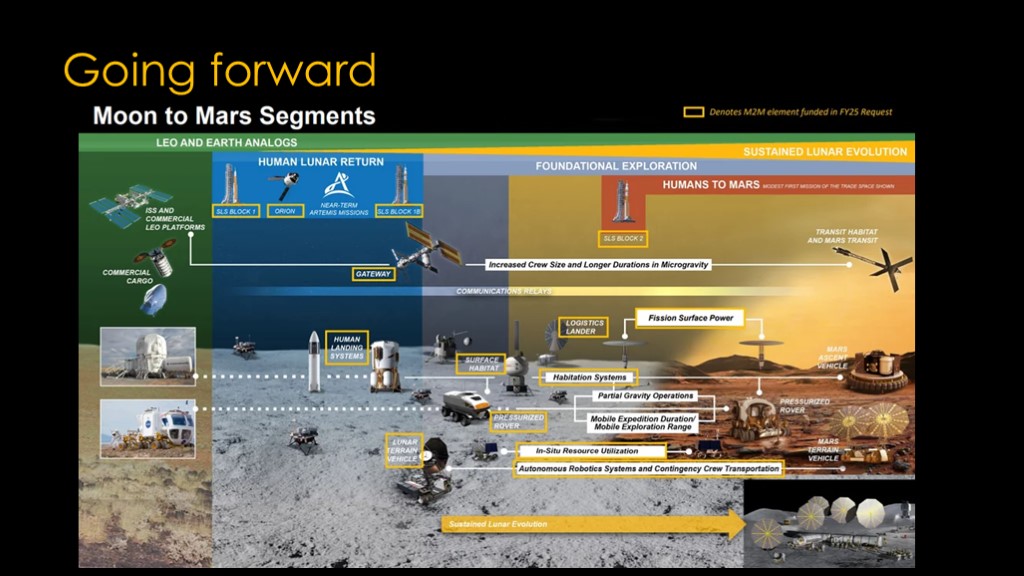

The second option is that NASA says "we've spent years and years studying humans in low earth orbit; let's take that money and spend it doing something more impactful".

The decision to move the money to exploration would obviously require the approval of congress, but it's pretty clear that the current exploration budget is not sufficient for the plans that NASA is showing here, despite what NASA says about the fiscal year 2025 request.

If you liked this video, you should know what to do...

This set 9030 piece set with hand-made items is available for only $759.